Measuring Urbanization: Why India Needs to Re-think its Methodology

by , , e -

This blog delves into the definition and measure of ‘urban’ in India to discuss the methodological gaps in existing definitions. It also looks at the advantages and limitations of a global method endorsed by the UN Statistical Commission for the delineation of urban, peri-urban and rural areas.

Earlier this year, India surpassed China to become the most populous country in the world. With 68% of the world population projected to live in urban areas by 2050, India is expected to see an additional 416 million urban dwellers. As India gears up for the next decadal census, it is critical to ensure that ‘urban’ in India is defined and measured accurately and effectively.

The definition of what constitutes ‘urban’ in India is often seen as conservative and is based on criteria formulated in 1961. Post-Independence, India was largely a rural economy going through social, political and economic turmoil. Consequently, the agricultural sector was accorded priority to further the development of the newly minted state. In this socio-economic backdrop, the criteria chosen to delineate rural and urban areas were supposed to prevent inflation of the country’s urbanization to prevent the diversion of funds from the priority agricultural sector.

However, India is today the 5th largest economy in the world and its socio-economic landscape has changed with cities emerging as the loci of economic growth. The urban-rural classification is the cornerstone for policy and program design, development planning, financial allocation, administrative and governance systems, and research in India. An inadequate definition and methodology for measuring urbanization may lead to unplanned development, misallocation of funds and inaccurate provisioning of public goods and services.

India’s Current Definition of Urban

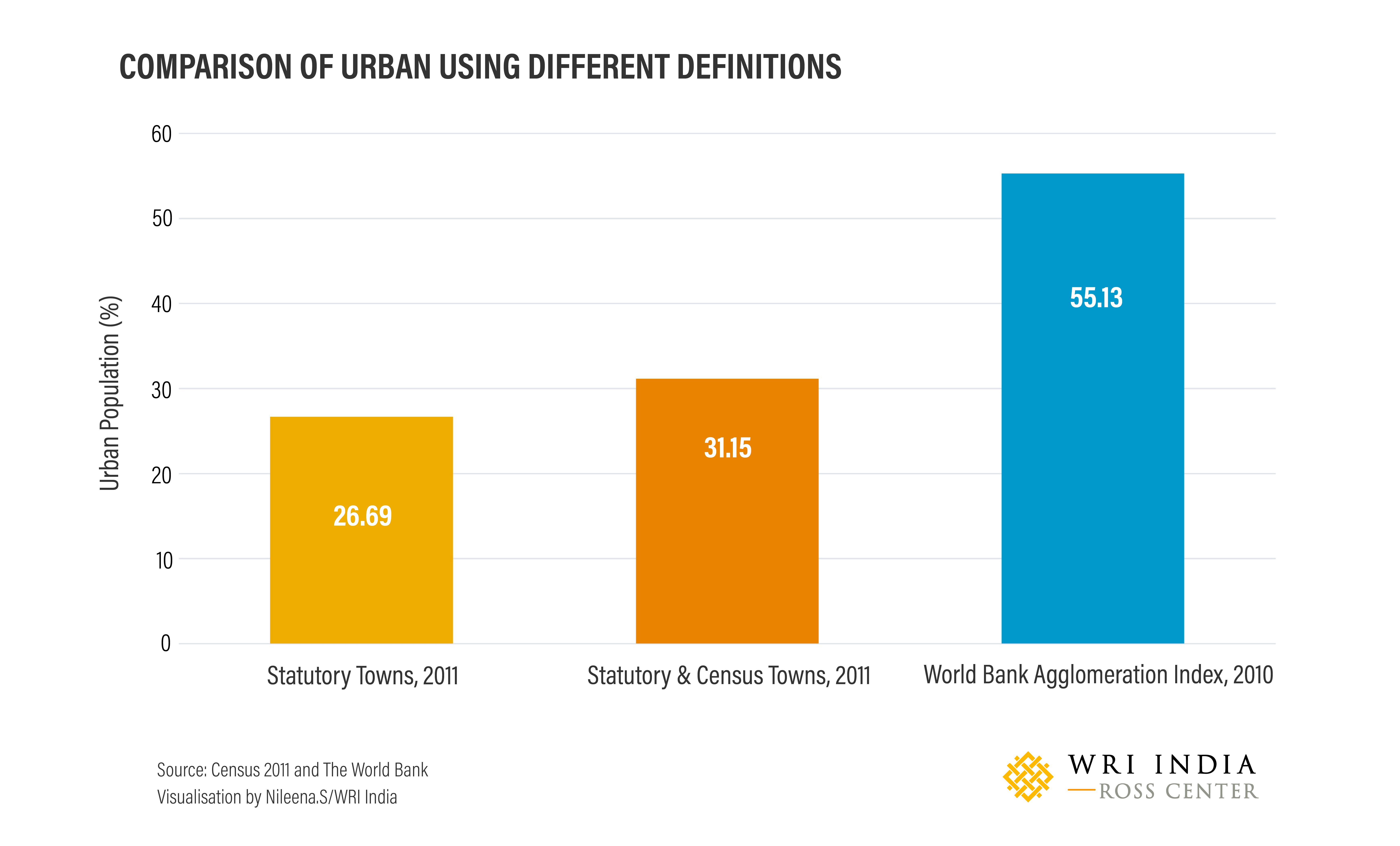

The Office of the Registrar General of India recognizes urban administrative units such as municipal corporations, municipalities, cantonment boards or notified town area committees to be ‘Statutory Towns’. Additionally, all other places that satisfy all three criteria – minimum population of 5000, population density greater than 400 person per square km and 75% male non-agricultural working population are classified as ‘Census Towns’ (Figure 1). States in India have in the past been encouraged by the Central Government to convert Census Towns to Statutory Towns. By the current definitions, only 31.2% of India is considered urban, and it has been strongly argued that this is less than the actual scale of urbanization.

This definition of “urban” used in India is considered particularly restrictive because it considers all three criteria – i.e. population size, population density and economic parameters. Most countries follow just one or two criteria, typically ranging from administrative, demographic, density (population and built-up) and economic activity to physical characteristics and levels of infrastructure.

The World Bank, using an alternative global method to measure urbanization known as the Agglomeration Index, observed that the “share of India’s population living in areas with urban-like features in 2010 was 55.3%”. This indicates hidden or missing urbanization unfolding on the peripheries of major cities or out of the administrative boundaries of statutory towns that needs further investigation. This method, however, could not be scaled up for use globally as it relies on population size, population density and commuting time to the nearest large urban center; and consistent and comparable commute data is not available at a global scale.

Degree of Urbanization - A Global Definition of Cities, Urban, and Rural

There is no standard global definition of ‘urban’. The lack of a harmonized definition makes it difficult to conduct cross-national comparisons and learnings about the extent of urbanization, performance of urban areas, Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) indicators, level of development, effectiveness of policies, etc. To address this problem, six international organizations – the European Union, The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the International Labour Organization (ILO), the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) and the World Bank, collectively developed a harmonized method for delineation of cities, urban, and rural areas, known as Degree of Urbanization (DEGURBA). This was endorsed by the UN Statistical Commission at the 51st Session held in March 2020 as the recommended method for international and regional statistical comparisons of urbanization.

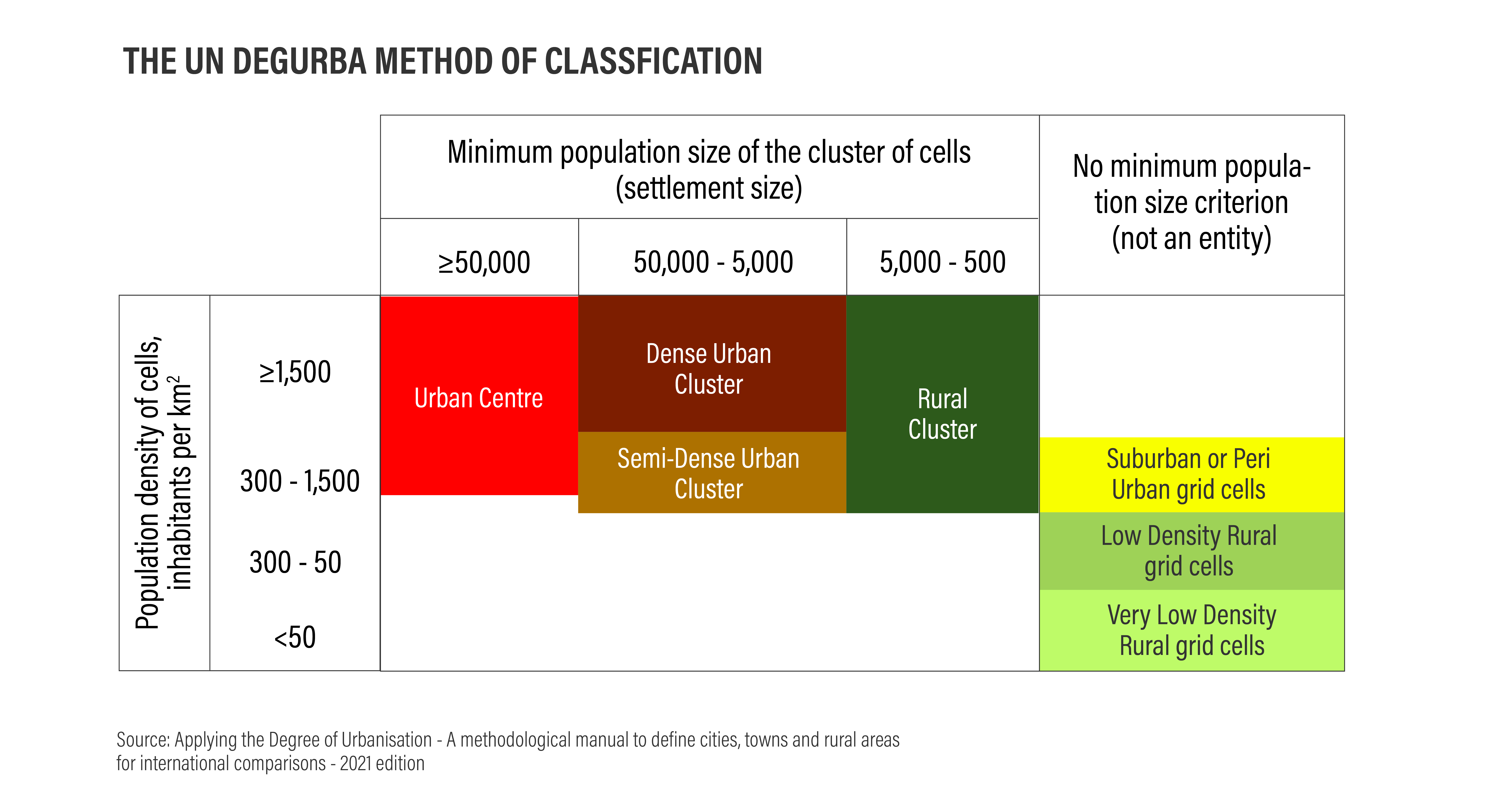

DEGURBA uses high-resolution satellite imagery to classify the entire territory of a country into three broad classes and seven sub-classes as follows (Figure 3):

- Urban center

- Urban cluster with sub-classes of dense urban cluster, semi-dense urban cluster and suburban or peri-urban cells

- Rural areas with sub-classes of rural clusters, low-density rural grid cells and very low-density rural grid cells

This method provides seven sub-categorizations of settlements as compared to the two categorizations of urban and rural employed by the Census of India. This could potentially provide an enhanced understanding of a settlement’s characteristics, detect problems, and financial resource targeting post-testing of the method for India.

This method recognizes the true spatial extent of urban agglomerations by using population grids of 1 km2, rather than being restricted by the variable size of statistical and administrative boundaries. The DEGURBA approach captures the spatial concentration of people directly by combining built-up area and census population into pixel data. Broadly, this method recognizes areas that are more suitable for monitoring access to services and infrastructure based on varying population sizes and densities.

Limitations of the DEGURBA method include a very low urban density threshold which can result in the classification of entire cropland regions, as well as more lightly populated fringe areas of cities, as urban. Additionally, since it is based on an algorithm and machine learning, there are certain limitations such as under-detection or over-detection of the built-up area, lack of differentiation between different types of built-up areas and inclusion of the inaccuracies inherited from the base data sources.

As India gears up to conduct its Census enumeration, despite its limitations, alternatives like the DEGURBA method merit attention as it goes beyond the urban-rural dichotomy. Researchers at WRI India are currently testing this approach and will share the findings in a working paper on its relevance and adaptability to the Indian context.

Shahena Khan is a Consultant with the Sustainable Cities and Transport team at WRI India.

Visualizations by Nileena S./WRI India and Map by Vinamra B./WRI India.

All views expressed by the authors are personal.