Agrivoltaics: Reimagining Land for Better Livelihoods

A version of this photo blog was originally published on October 15, 2024 in Gaon Connection.

As the first light of dawn breaks over the farm, Ravi steps onto the field to the sight of solar panels glistening under the early morning sun. This is no ordinary farm; it is an agrivoltaics installation where the land is co-utilized for cultivating crops, raising livestock and harnessing solar energy.

Ravi and his co-worker Rajesh oversee this 2.5 MW solar plant, spread over 3.4 acres of land in Issapur, on the outskirts of Delhi. The knowledge and skills from their previous work in agricultural universities comes in handy. They grow a range of horticultural crops on the farm, including fruits, vegetables, spices and livestock feed. This innovative approach not only maximizes land use but also enhances the sustainability of local farming practices.

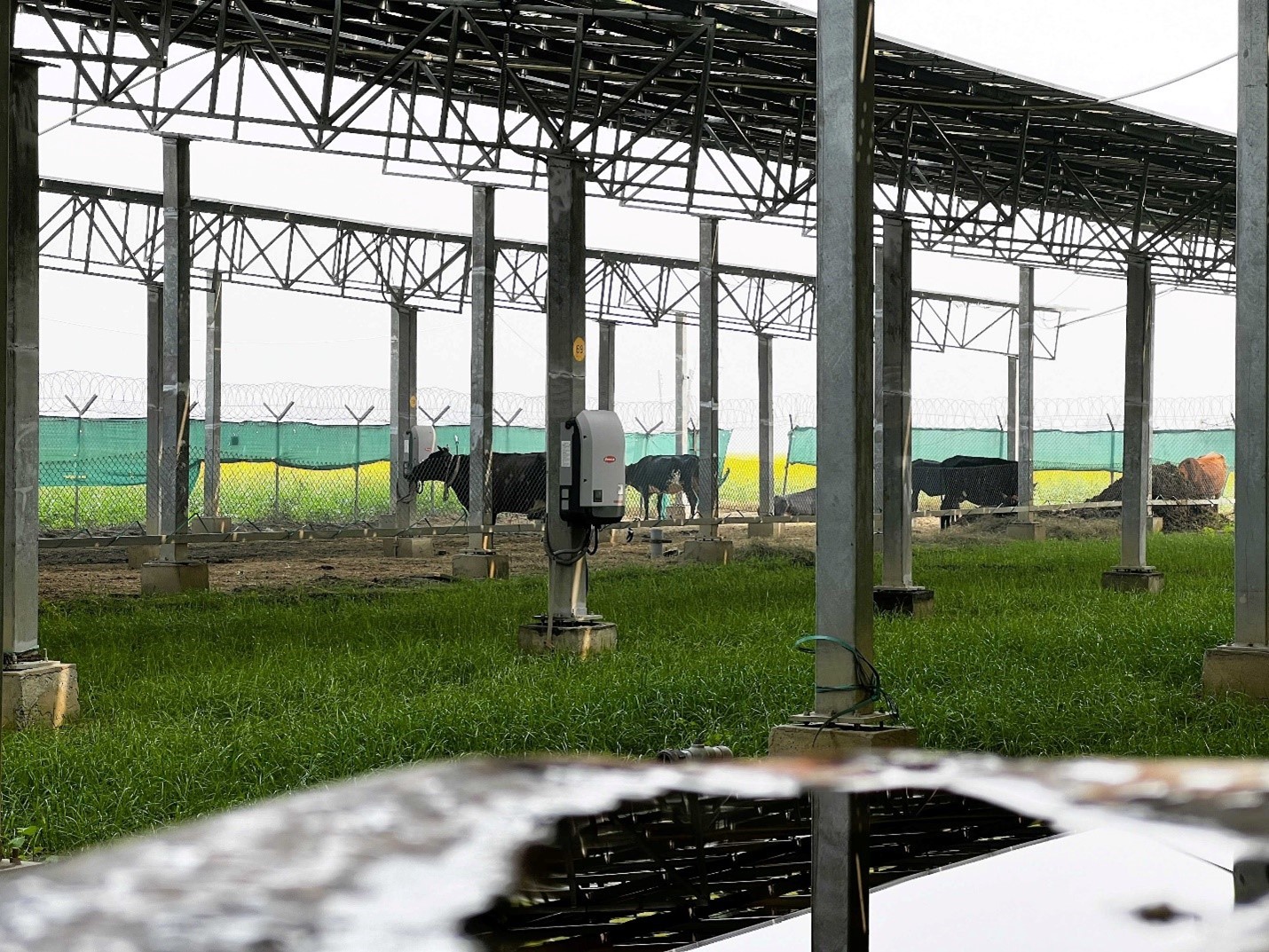

Additionally, the Issapur agrivoltaic plant houses a herd of 8-10 cattle that are reared in a dedicated space, under the solar panels, where they can graze. This practice, known as solar grazing, allows farmers to diversify their income while also generating renewable power.

Agrivoltaics plants can offer employment opportunities for the local community, sometimes supplementing their existing income between sowing and harvesting seasons. Kuldeep, a local farmer, cultivates mustard on an adjacent farm while also working as a laborer on the agrivoltaics plant. He said that the installation has been a boon for agricultural laborers like him, who do not get much work between the sowing and harvesting seasons. The cultivation of various short-term, shade-loving crops at the plant generates a regular demand for agricultural work, offering workers like Kuldeep greater economic opportunities.

“खेती और सोलर साथ में करने से 2 और चूल्हे जल जायेंगे तो सब के लिए अच्छा ही है ना?” – कुलदीप (translation) “It is good for everyone if farming and solar power generation can together generate income for two more families.” - Kuldeep

Apart from the four to five workers engaged in farming activities, the plant also employs three to four workers to maintain and operate the solar panels. Currently, only one of these workers is a woman.

Co-locating solar and agricultural activities has the potential to sustain and improve women’s livelihoods, who make up two-thirds of India’s agricultural workforce. Laxmidevi, who has been with the plant since its inception in 2021, lost her previous job at a local factory during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Issapur plant provided her with the opportunity to earn a stable income within her village.

Today, she manages the farm’s livestock and the land surrounding the panels and plays a key role in the day-to-day operations of the plant. She has been trained to assist in the activation of the solar PV system, which produces power that is directly fed into the grid. In a largely male-dominated field, initiatives to train women in agrivoltaics play a crucial role in fostering a more inclusive technological transition. As technology scales up, providing training to local agricultural workers — especially women — to become solar technicians can contribute to preserving and improving their livelihoods.

In addition to the socio-economic benefits of job creation and livelihood preservation, agrivoltaics can be environmentally beneficial. Shade from the solar panels can increase water-use efficiency by reducing the water lost through evaporation, which is particularly advantageous in arid and semi-arid regions. Additionally, the water used to clean solar panels can be repurposed for irrigation, as seen at the Cochin International Airport agrivoltaic plant.

Setting up an agrivoltaics plant may require farmers to alter their crop choices and restructure existing practices and farming schedules. Such changes require additional effort and investment that aren’t always viable for farmers.

Mohan, another local farmer, chose not to set up an agrivoltaics plant on his farmland due to the high upfront cost. He was unsure about changing the crop and land use, and did not see a clear incentive to change something that was working well. This is where agriculture extension centers or Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs) can play a pivotal role.

For example, the KVK at Ujwa village in Delhi has a pilot-scale demonstration unit that provides scientific evidence to farmers on the benefits and practical challenges of agrivoltaics.

In Amrol, Gujarat, Prof. Mevada’s team from Anand Agricultural University has successfully cultivated more than 30 varieties of crops, including cereals, pulses and oilseeds, at their 1 MW plant. Effective dissemination of findings, from existing and upcoming pilot installations across different agroecological zones, can help farmers make informed decisions about adopting agrivoltaics.

Models like Issapur and the stories of its workers can be useful for farmers and developers exploring agrivoltaics across the country. More importantly, achieving a just and equitable transition to low-carbon technologies requires dedicated supportive policies on shared land use for agriculture and solar PV.

At present, the only policy framework guiding farmers in installing solar plants on their agricultural land is the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Utthaan Mahabhiyan Yojana (PM KUSUM), that supports the solarization of rural and agricultural feeders. Small and marginal farmers who are already in financial distress might get left behind during the scaling-up process due to the high upfront investment and the fixed nature of the installation. Moreover, agrivoltaics are suitable only for certain land and crop types, thereby excluding landowners whose land and soil characteristics do not align with these requirements. Thus, detailed and clearly defined standards and regulations are needed to incentivize small and marginal farmers and support them in adopting agrivoltaics at scale. These regulations must be informed not just by learnings from entities like KVKs, academic institutions and solar developers, but also by insights from farmers and workers who are directly affected.

A people-centered approach must account for the perceptions, preferences and priorities of key stakeholders, particularly farmers and local communities, who will need support to make the most of this transition. This support should include the development of a diverse set of skills to implement and maintain agrivoltaic systems. Furthermore, highlighting farmers’ experiences and incorporating their values and concerns in project planning and regulation will be key to developing agrivoltaics in a just and equitable manner. Exploring financial and benefit-sharing mechanisms, such as the possibility of pooling land and resources for agrivoltaics, is another way to ensure the accessibility of agrivoltaics to farmers of all classes and an equitable distribution of its benefits.

Agrivoltaics presents an opportunity to optimize land use and reimagine the food-energy-water nexus. However, its success lies not only in the technology but how it is implemented and the impact it could have on people who depend on land-based livelihoods. By placing the needs of farmers and rural communities at the forefront, agrivoltaics holds the potential to advance India's journey towards achieving both energy and food security, equitably.

The names of all the workers mentioned in the photo essay have been changed to ensure their anonymity. Vishwajeet Poojary is a former Senior Program Associate, WRI India.