How Indian Cities Could Become Climate Resilient

by e -

This blog first appeared on NIUA.org on August 4, 2021.

India’s buildings were responsible for 31% of all electricity consumed in 2017-18 (MOSPI 2020) and by 2040, this is expected to rise to half of all power consumed in the country. By 2040, India is expected to add 270 million people to its cities (IEA 2021). What is more, ongoing rapid urbanization would mean that over half the country’s population would be living in cities in less than two decades, from less than one-third in 2011 (31.7%)

These national level projections must be supported by a more granular understanding of buildings’ energy consumption and resource demand in cities, growth patterns of different construction typologies and power needed for different energy services (for example: cooling, heating, lighting). Robust urban buildings sector data will be critical inputs in India’s response to climate change and to strengthen participation of cities in the energy transition. Transparency in this data helps track, and report progress on indicators and targets, engage citizens in the process and supports implementation of building-sector decarbonization policies and programs.

Building sector data not identified as priority at subnational level.

However, collection of building sector data has not been prioritized. Data on the size, age and quality of building stock, the different types of buildings, building materials most commonly used, combined with their energy use and performance characteristics can be collected regularly and systematically at the city-level. For the collection of property taxes, urban local bodies have records of existing buildings and new ones that are being added. But in many cases, these records are fragmented and distributed across multiple divisional offices in the city, and any altered use or building type is usually not updated, posing problems for compilation.

Weaknesses in the buildings data management system

There are three reasons for the weaknesses in urban buildings data management system.

First, cities often collect data based on directions from state governments. Sometimes the state’s statistics departments collect data from Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) as directed by other departments. Therefore, unless explicitly identified as useful for the state for policy making or program design, cities do not prioritize buildings data collection.

Second, the speed of urban development has outpaced the institutional capacity to collect the required data. Data is collected at multiple levels by different city agencies for their respective objectives, with no common identifier between datasets.

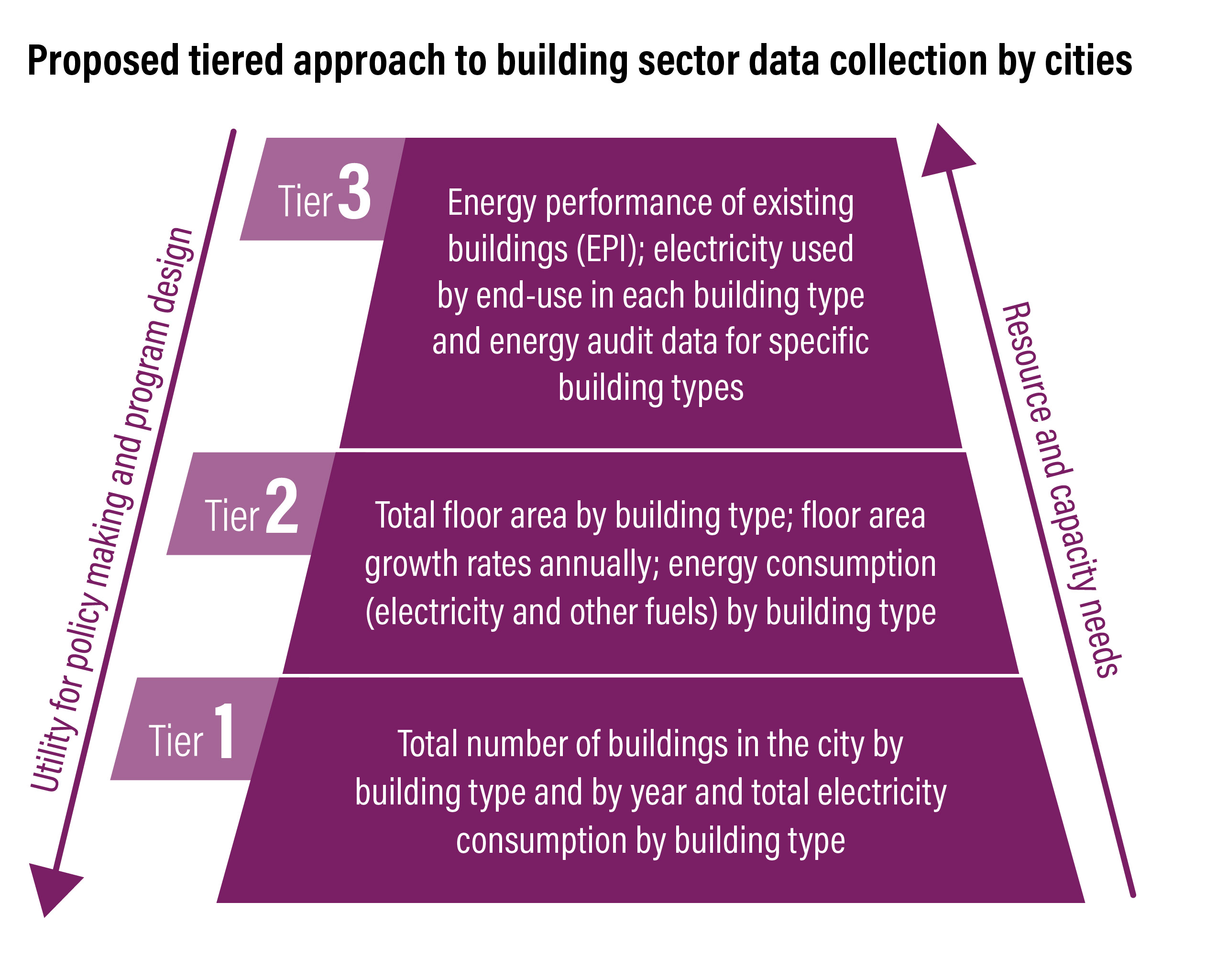

A tiered approach to data collection

Buildings’ data presents cities an untapped potential in the formulation of climate mitigation and adaptation interventions. Cities can directly use information like built up area, or building type and materials, for climate proofing building stock. For example, disaster risks planning could use better data on type of materials in existing structures to inform planners on buildings that are susceptible to structural damage during extreme weather. Spatially mapped buildings datasets can help in identifying locations in the city prone to urban heat island effects. Similarly, building sector data could be useful in reducing emissions. This data could help identify buildings or neighborhoods to promote energy efficiency measures, circularity, transit planning, and water supply to communities

How can this data collection process start?

First, an all or nothing approach to collect building stock and energy data is unwise. Second, any data collection efforts must address the capacity constraints in Indian cities and limited professional expertise in data collection and analysis. Cities can consider a tiered approach

Indian cities could consider the following criteria to operationalize data collection initiatives:

- Application: Cities must collect data based on their well-defined priorities, needs and applications. For example, is the municipality interested in understanding energy use in its own buildings and fix energy saving targets? Or the other way round, that is, the corporation has committed to a 10% energy use reduction target and would like to collect data to identify buildings with the highest energy saving opportunities? Is the city motivated to build resilience of low income housing? Cities may also be driven by applying this data to meet reporting requirements under national initiatives like, Climate Smart Cities Assessment Framework, or as signatories to programs like Global Convenant of Mayors. Systematic collection of building sector data will be a win-win for cities and support state government’s reporting and tracking of indicators.

- Availability: Cities can start with what they already have. For example, through digital records of property taxes, they can aggregate information on total floors/built-up area. Existing GIS data on building footprint can be combined with climate vulnerability maps to assess vulnerable parts of the city’s building stock. Cities must continue to look at approaches to improve data availability over time. For new buildings being constructed every year, new data fields in municipal forms to obtain an occupancy certificates can be added to obtain energy-related information for new buildings. For example, the sanctioned electricity load of the building, allocation of roof space to solar energy generation as per the sanctioned building plan.

- Resources: Depending on the status of the two criteria above, cities may need to invest in additional staffing or allocate separate budgets for data collection. Cities with strong state government departments of statistics and planning could seek support in creation of methodological frameworks. The position of Chief Data Officers (CDOs) created under Smart Cities Mission can be strengthened and converted into a city data office, which regularly captures data on built environment. Finally, civil society organizations could be engaged to build open-source platforms, mobilize grassroots initiatives to collect data on the buildings at the neighborhood scale, which will further strengthen policy engagement with citizens.

Indian cities must take a hard look at their building stock and ways to manage their unsustainable demand for resources. By prioritizing the right kinds of datasets, cities can enhance their contributions to transition to cleaner sources of energy and their efficient use. They would also witness significant savings on power and could become more climate resilient.

Views expressed are personal.