Exploring Payment Security Mechanism for E-Bus Expansion

by and -

India’s public transport landscape is rapidly transitioning from conventional Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) buses to electric buses (e-buses). The country’s aspiration to decarbonize road transport by scaling-up adoption of e-buses has been bolstered by the PM-eBus Sewa Scheme. Announced by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) in August 2023, the scheme aims to deploy 10,000 e-buses across 169 eligible small and medium cities through central financial assistance. With over 16,000 buses in various stages of procurement, ensuring payment security for operators in this capital-intensive industry assumes greater significance.

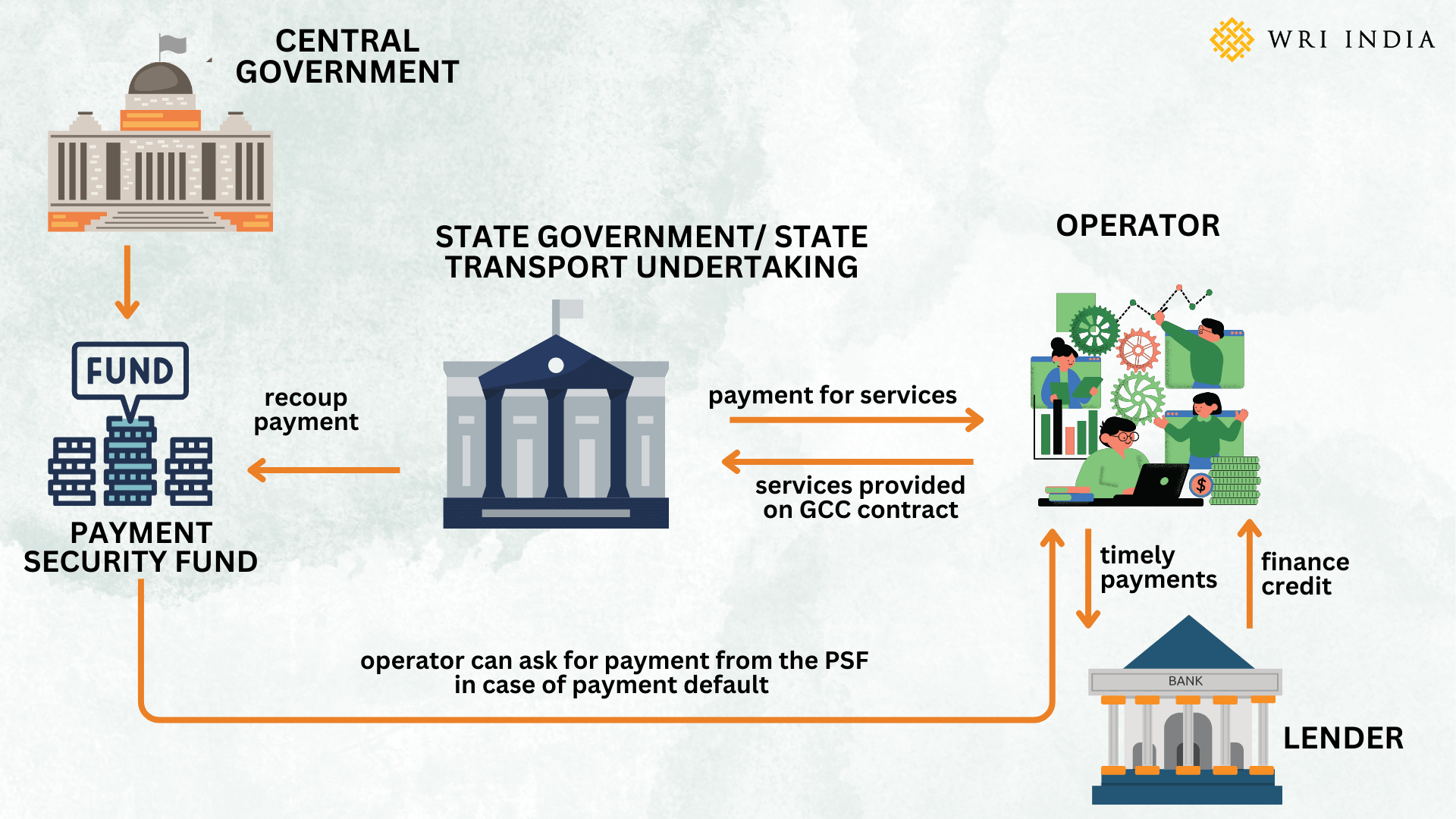

Under the prevalent model of Gross Cost Contracting (GCC), transit authorities take the risk of ridership and farebox revenues while the selected operator takes the risk of financing buses and allied infrastructure, technology, operations and asset performance. Urban operators typically only recover 32% of the operating costs through fare box revenue. The PM e-bus Sewa’s operational Viability Gap Funding (VGF) allows authorities to bridge this gap in operating costs by availing assistance on a per km basis for providing services. However, authorities rely on additional funds from the state or urban local bodies, and delays in budgetary sanctions and fund release result in delayed payments to operators. This creates a significant hurdle that dampens market sentiment and discourages wider participation from large and medium-scale operators.

To boost electric mobility efforts, in June 2023, India and the United States came together to provide joint support for a payment security mechanism (PSM) financed through both public and private funds. This offered a significant push towards accelerating the procurement of 10,000 e-buses in India.

The Need for a Robust Payment Security Mechanism (PSM)

E-bus operators in India are mostly financed through debt from commercial banks with financing provided against the balance sheet of the operating company. This is often backed by corporate guarantees of the parent Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs). Payment delays by authorities make timely debt servicing difficult for operators who often rely on working capital financing for managing the cashflow shortfall. Additionally, the existing recourse-based lending – which allows lenders to pursue either additional assets beyond project collaterals when a borrower defaults or even pursue the corporate guarantees of the parent OEM – limits the operator’s capacity for taking up new projects. Payment security mechanisms that kick in when transit authorities are unable to make timely payment to the operators can help de-risk the e-bus sector for the operators. Existing PSMs, such as escrow facilities that are common to public contracts, across industries, are often not well implemented. The absence of other mechanisms has led the industry to advocate for improved bankability of e-bus projects through innovative payment security mechanisms.

The recently announced Payment Security Fund (PSF) partly capitalized through United States grants and under development by Ministry of Heavy Industries (MHI) is an affirmative step towards addressing bankability concerns for lenders and borrowers, especially for smaller cities with little to no experience in managing public transport. It will aid the scaling up of services and strengthen the private sector’s ability to cater to the high decarbonization ambitions of the sector. The design of the PSF also provides the opportunity to improve efficiency, service delivery and fiscal management for Public Transit Agencies (PTAs) and digitization in the sector. The PSF could consider the following recommendations to have a higher impact on the public transport sector.

- A permanent but flexible PSF managed by a central entity must be established covering the National Electric Bus Program’s (NEBP) future contracts beyond the announced initial 25,000 e-bus procurement by MHI. This will signal a long-term commitment by the Indian Government and will strengthen private investments in the sector.

- The fund should allow other grants and low-cost capital, such as credit guarantee structures provided by multilateral development banks. Other forms of blended finance to enhance coverage of the PSF should also be permitted.

- Ideally, the fund should be revolving, with the defaults being replenished by the state to ensure the sustainability of the mechanism. A similar mechanism in the renewable power generation sector under Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) has ensured lower defaults and easier private financing.

- Digitalization of invoicing, service-level agreement monitoring, and payment processing should be introduced to ensure monitoring of contracts, dispute resolution and timely payments to operators.

- The existing lack of financial data and transaction history of transit agencies hamper lenders’ assessment of risks in the sector. The proposed PSM should aim to set up a database of payment history and possibly credit ratings for participating agencies, enhancing bankability of projects through an informed risk-assessment framework.

In the long term, financial reforms for public transport agencies with sustained funding through state level schemes such as the Chief Minister’s Urban Bus Service Scheme (CMUBS) in Gujarat, are required for the public transport sector. However, the proposed centralized PSF has the potential to support transit agencies, which are constrained by finances, and boost the investment confidence of commercial lenders and private operators. This can play a critical role in the expansion of e-bus services, enabling India to decarbonize its public transport sector.

All views expressed by the authors are personal.