Can Greening be Prioritized in Vulnerable Neighborhoods?

This blog highlights the challenges and opportunities for greening for climate action in low-income communities by looking at three neighborhoods in Mumbai: Lallubhai compound, Cheeta camp and Ambujwadi.

“I live in an area that has barely any trees. There is little shade and during very hot days, I feel tired and dizzy,” sighs Priya Shinde, a resident of Lallubhai compound. Every day, Priya walks to the nearby school where she teaches. There is no respite from the heat at the school either, as the children and the staff bear the brunt of hot metal roofs, little to no ventilation and fans that barely run due to the erratic electricity supply.

Lallubhai compound, a rehabilitation and resettlement (R&R) colony in M-East Ward, witnesses surface temperatures often exceeding 35 °C during summers. This is not uncommon for high-density, self-organized, low-income settlements with metal sheet roofs and little to no vegetation cover.

An avid gardener, Priya has built a small balcony garden, creating a cooler microclimate for her immediate surroundings. She often includes children in gardening activities, passing on her knowledge of micro-greening to her community.

Over the past year, WRI India, along with Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action (YUVA) and Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) identified high-heat risk zones across Mumbai to further scientific greening as a climate adaptation strategy, supported by on-ground community stewardship.

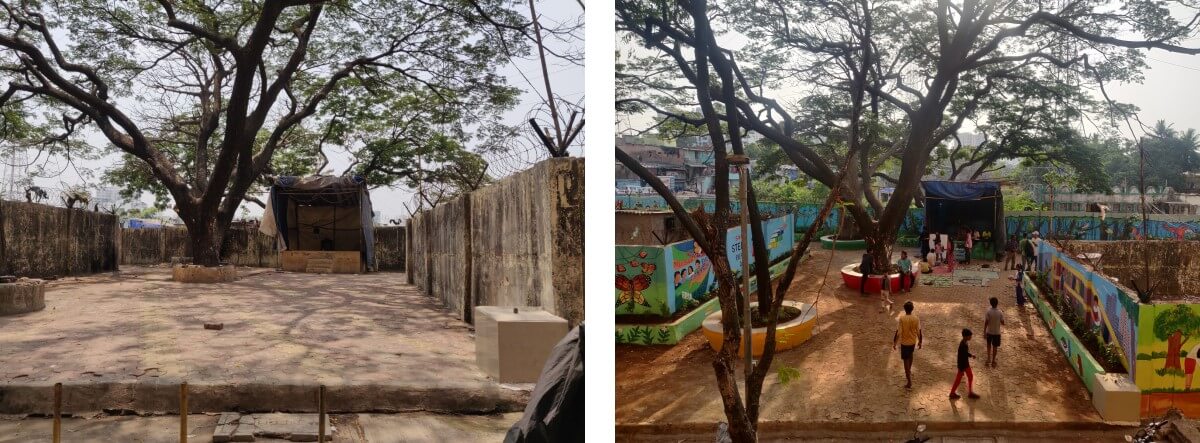

These projects have successfully transformed neglected areas by creating a sense of ownership and building confidence within the community to scale these interventions to other areas that need attention.

During our engagements, we observed several factors that added to vulnerabilities in these neighborhoods:

1. Lack of Open Spaces: The lands reserved for recreational grounds, parks and maidans are inadequate for the population that they serve. The Development Plan 2034 shows that only half a square meter of open space per person is available in M-East Ward,considerably short of the four square meter benchmark it sets for Greater Mumbai. Additionally, open spaces often end up being used as car parks and garbage dumps while wide open areas like maidans are often disconnected from the community’s needs – for example, at one location, a sports club took over the space which failed to take into account the requirements of senior citizens, women and toddlers, amongst others.

Possible Solutions: Communities, along with technical experts, can identify spaces that can be leveraged for greening. Incorporating micro-greening activities on roofs, windows, footpaths, society compounds, etc., can also be considered.

2. Lack of Water: Most vulnerable settlements lack access to adequate water supply. According to Shehenshah Ansari, a community organizer at YUVA, who has been living in Mumbai’s Ambujwadi since 2007, “Water connections have been provided by the local municipality but we get supply for just an hour a day (30 minutes in the daytime and 30 minutes late at night), where one connection is shared by five households. A total of 200 liters is received if the tap is supported by a motor, 100 liters or less without one. Additional water, which is unfiltered and sourced from borewells and wells, needs to be purchased from vendors at about Rs 30 to 40 for 40 liters.” The national benchmark for access to water is 135 liters per capita per day – far above what is available in Ambujwadi. Water for greening is consequently a low priority for these neighborhoods.

Possible Solutions: Alternatives including the setting up of a mini-sewage treatment plant for recycling wastewater and stormwater, and rainwater harvesting during monsoons. Coordinated efforts between government departments can help ascertain the feasibility of using filtered water from stormwater drains/sewage water for greening.

3. Motivation for Community Engagement: Communities lack a sense of ownership if they are excluded from the design, execution and maintenance of their area’s limited public spaces. As a result, spaces are underused, misused or abandoned.

Sagar Chandrashekar Reddy, a member of Bal Adhikar Sangharsha Sanghatan (BASS), a local youth group, says, “We rarely visited these areas as they were perceived to be unsafe. We were able to share our ideas and co-create a green community space by working with biodiversity and design professionals to really transform it into a place that everyone is proud of. We can connect with each other better! Being a part of this process also taught me a lot about planting methods.

4. Lack of Policies to Regulate Scientific Greening by Citizens: While there is no shortage of interest among citizens, they are faced with challenges relating to resources, approvals and lack of scientific knowledge. For example, a plantation effort by a community in the P-North ward had previously failed due to an incompatible plant choice for the local soil profile.

Possible Solutions: The project adopted ways to increase awareness about local greening practices, sharing stepwise, scientific solutions on how to increase biodiversity. Integrating this knowledge into a user-friendly guidance document is one way to scale up micro-greening programs. Platforms for multi-stakeholder engagement can further help identify context-specific gaps to discuss collaborative ways to inform guidelines.

5. Lack of Funding: Procuring funds such as those from Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) donations, local corporators and funds under special projects, poses many challenges. These include a lack of evidence of previously successful interventions, and tenure and land ownership conflicts.

Possible Solutions: For the sustenance of the greening sites, an economic and legal model is currently being explored wherein community members can take ownership of funds allotted for welfare projects and guidance from an NGO to create long-term sustenance plans

These greening pilots have become examples of how community stewardship with multi-stakeholder support can influence the ecological transformation of barren spaces, enabling the scaling up of similar interventions.

In the next blog, we will deep dive into how underused open spaces can be identified for scaling micro-greening initiatives.

All views expressed by the authors are personal.